We woke to a clear blue sky, birdsong, and a fantastic view down into the Trongsa Valley.

Keen to visit the local Dzong before our drive to Popjika Valley and a day of hiking, we left early after a quick breakfast.

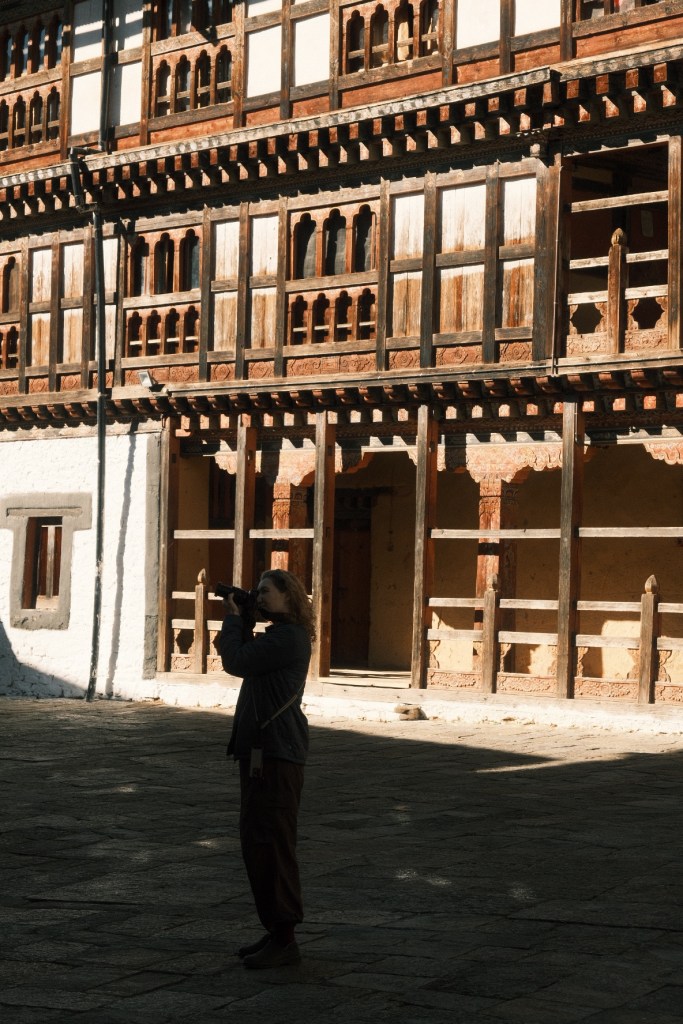

Every district in Bhutan has at least one Dzong (fortress).

These vary in size, age and importance from valley to valley, and the Trongsa Dzong is the largest in the country.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of Dzongs to country’s culture and history.

In fact, the bhutanese language is called Dzongkha, which roughly translates to “the language of the fortresses,” and districts are called Dzongkhag, literally translating to “fortress district.”

Bhutan has a long history of battling invasions from other Himalayan tribes and countries, —mainly Tibet and Mongols, as well as Indian separatists and internal uprisings— and so Dzongs were key to Bhutan’s existence and survival.

Bhutan itself was only ‘united’ in the 17th Century, to be ruled by a council of district governors, each residing in their district’s Dzong.

This persisted until the father of the first king started a civil war, concluded by his son in 1907, which established the Royal Family with the help of the East India Trading Company, keen to establish a direct trade route between India and Tibet.

The Dzongs remained.

No longer needed to ward off attacks, they became centers of governmental and monastic administration, and so each is divided into a civil and a religious section, with a temple and courtyard for local festivals.

into the valley itself — no longer in use

Leaving Trongsa in Central Bhutan and journeying further west we crossed two mountains (the first pass at 3,600m and the second at 3,200m asl) and descended into Phobjikha Valley, also known as Gangtey.

We ate lunch at a little home stay along the way, where the hostess served us various vegetarian dishes and hot milk tea.

Afterwards, we arrived in Phobjikha Valley, a warm high plateau at 3,000m asl that has become famous for being the one of 3 preferred wintering places for the Black Necked Cranes.

The relatively large birds live in regions of the Eastern Himalayas, breeding in the north-west of India, in Tibet, and Bhutan.

Over the years, up to 600 birds have been counted coming to Phobjikha to spend the winter (about 16,000 Black Neck Cranes are estimated worldwide).

To help these rare and beautiful birds, seen in Bhutan as connectors to the realms of the afterlife, the government has established a bird rehabilitation centre, and forbidden over-ground power-lines in the valley, as well as putting strict regulations on the expansion of the nearby farming village.

Usually, they arrive in mid-November to December, but we got very lucky and were able to count 11 birds. Our cameras do not have sufficient zoom for you to see them up close, but let us tell you: they are beautiful.

Once we’ve arrived at the hotel, we got ready for a relaxed hike through the valley and up to the Phobjikha monastery, located in the old village itself, before people relocated down into the valley, and overlooking a stunning landscape.

It was sunny, and the air smelled of pine needles and warm earth — we had a lovely time

Just as we weee staring to feel the effects of the altitude, we reached the monastery atop the village, where our driver was waiting.

It’s hard to capture in the photos, but every prayer wheel had stone-carved illustrations placed behind it, so that walking around the temple felt like watching an ancient story unfold.

It gets dark in Bhutan at around 5pm, so we returned to the hotel to have a cup of tea and watch the sunset in peace before heading to dinner and bed.

Leave a comment